General Information About Bladder Cancer

Incidence and Mortality

Bladder cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the United States after lung cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer, and melanoma. It is the fourth most common cancer in men and the eleventh most common cancer in women. Of the roughly 83,000 new cases annually, about 63,000 are in men and about 20,000 are in women. Of the roughly 17,000 annual deaths, more than 12,000 are in men and fewer than 5,000 are in women. The reasons for this disparity between the sexes are not well understood.[1,2]

Estimated new cases and deaths from bladder cancer in the United States in 2024:[2]

- New cases: 83,190.

- Deaths: 16,840.

Anatomy

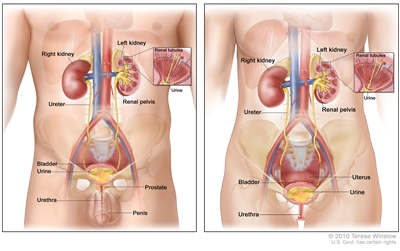

The urinary tract consists of the kidneys, the ureters, the bladder, and the urethra. The urinary tract is lined with transitional cell urothelium from the renal pelvis to the proximal urethra. Transitional cell carcinoma (also known as urothelial carcinoma) can develop anywhere along this pathway.

Anatomy of the male urinary system (left panel) and female urinary system (right panel) showing the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The inside of the left kidney shows the renal pelvis. An inset shows the renal tubules and urine. Also shown are the prostate and penis (left panel) and the uterus (right panel). Urine is made in the renal tubules and collects in the renal pelvis of each kidney. The urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the bladder. The urine is stored in the bladder until it leaves the body through the urethra.

Histopathology

Under normal conditions, the bladder, the lower part of the kidneys (the renal pelvises), the ureters, and the proximal urethra are lined with a specialized mucous membrane referred to as transitional epithelium (also called urothelium). Most cancers that form in these tissues are transitional cell carcinomas (also called urothelial carcinomas) that derive from transitional epithelium. For more information, see Renal Cell Cancer Treatment and Transitional Cell Cancer of the Renal Pelvis and Ureter Treatment.

Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder can be low-grade or high-grade:

-

Low-grade bladder cancer often recurs in the bladder after treatment but rarely invades the muscular wall of the bladder or spreads to other parts of the body. Patients rarely die of low-grade bladder cancer.

-

High-grade bladder cancer commonly recurs in the bladder and has a strong tendency to invade the muscular wall of the bladder and spread to other parts of the body. High-grade bladder cancer is treated more aggressively than low-grade bladder cancer and is much more likely to cause death. Almost all deaths from bladder cancer result from high-grade disease.

Bladder cancer is also divided into muscle-invasive and nonmuscle-invasive disease, based on invasion of the muscularis propria (also known as the detrusor muscle), which is the thick muscle deep in the bladder wall.

-

Muscle-invasive disease is much more likely to spread to other parts of the body and is generally treated by either removing the bladder or treating the bladder with radiation and chemotherapy. As noted above, high-grade cancers are much more likely to be muscle-invasive than low-grade cancers. Thus, muscle-invasive cancers are generally treated more aggressively than nonmuscle-invasive cancers.

-

Nonmuscle-invasive disease can often be treated by removing the tumor(s) via a transurethral approach. Sometimes chemotherapy or other treatments are introduced into the bladder with a catheter to help fight the cancer.

Under conditions of chronic inflammation, such as infection of the bladder with the Schistosoma haematobium parasite, squamous metaplasia may occur in the bladder. The incidence of squamous cell carcinomas of the bladder is higher under conditions of chronic inflammation than is otherwise seen. In addition to transitional cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and sarcomas can form in the bladder. In the United States, transitional cell carcinomas represent most (>90%) bladder cancers. However, a significant number of transitional cell carcinomas have areas of squamous cell or other differentiation.

Carcinogenesis and Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors for bladder cancer include the following:

- Use of tobacco, especially cigarettes.[3]

- Family history of bladder cancer.[4]

- Genetic mutations.[5,6,7]

- HRAS mutation (Costello syndrome, facio-cutaneous-skeletal syndrome).

- Rb1 mutation.

- PTEN/MMAC1 mutation (Cowden syndrome).

- NAT2 slow acetylator phenotype.

- GSTM1 null phenotype.

- Occupational exposure to chemicals in processed paint, dye, metal, and petroleum products that include:

- Aluminum production (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, fluorides).[3]

- Aminobiphenyl and its metabolites.[3]

- Aromatic amines, benzidine and its derivatives.[3]

- Certain aldehydes.[8]

- 2-Naphthylamine, beta-naphthylamine.[3]

- o-Toluidine.[9]

- Treatment with cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, or pelvic radiation for other malignancies.[10,11,12]

- Use of Chinese herbs: aristolochic acid extracted from species of Aristolochia fangchi.[13]

- Exposure to arsenic.

- Arsenic in well water.[14,15,3]

- Inorganic arsenic compounds (gallium arsenide).

- Exposure to chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons and chlorination by-products in treated water.[16]

- Schistosoma haematobium bladder infections (bilharzial bladder cancer).[17]

- Neurogenic bladder and associated use of indwelling catheters.[18]

There is strong evidence linking exposure to carcinogens to bladder cancer. The most common risk factor for bladder cancer in the United States is cigarette smoking. It is estimated that up to one-half of all bladder cancers are caused by cigarette smoking and that smoking increases a person's risk of bladder cancer two to four times above baseline risk.[19,20] Smokers with less functional polymorphisms of N-acetyltransferase-2 (known as slow acetylators) have a higher risk of bladder cancer than other smokers, presumably because of their reduced ability to detoxify carcinogens.

Certain occupational exposures have also been linked to bladder cancer, and higher rates of bladder cancer have been reported in textile dye and rubber tire industries; among painters; leather workers; shoemakers; and aluminum-, iron-, and steelworkers. Specific chemicals linked to bladder carcinogenesis include beta-naphthylamine, 4-aminobiphenyl, and benzidine. Although these chemicals are now generally banned in Western countries, many other chemicals still in use are also suspected of causing bladder cancer.[20]

Exposure to the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide has also been associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer.

Chronic urinary tract infections and infection with the parasite S. haematobium have also been associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer, often squamous cell carcinomas. Chronic inflammation is thought to play a key role in carcinogenesis in these settings.

Clinical Features

Bladder cancer typically presents with gross or microscopic hematuria. Less commonly, patients may complain of urinary frequency, nocturia, and dysuria, symptoms that are more common in patients with carcinoma in situ. Patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas may present with pain resulting from obstruction by the tumor.

Urothelial carcinomas are often multifocal—the entire urothelium needs to be evaluated if a tumor is found. In patients with bladder cancer, upper urinary tract imaging is essential for staging and surveillance. This can be accomplished with ureteroscopy, retrograde pyelograms during cystoscopy, intravenous pyelograms, or computed tomography (CT) urograms. Similarly, patients with an upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma have a high risk of developing bladder cancer; these patients need periodic cystoscopy and surveillance of the contralateral upper urinary tract.

Diagnostics

When bladder cancer is suspected, the most useful diagnostic test is cystoscopy. Radiological studies such as CT scans or ultrasound do not have sufficient sensitivity to be useful for detecting bladder cancers. Cystoscopy can be performed in a urology clinic.

If cancer is seen on cystoscopy, the patient is typically scheduled for bimanual examination under anesthesia and a repeat cystoscopy in an operating room so that transurethral resection of the tumor(s) and/or biopsies can be performed. If a high-grade cancer (including carcinoma in situ) or invasive cancer is seen, the patient is staged with a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (or CT urogram) and either a chest x-ray or chest CT scan. Patients with a nonhepatic elevation of alkaline phosphatase or symptoms suggestive of bone metastases undergo a bone scan.

Prognostic Factors

The major prognostic factors in carcinoma of the bladder are the following:

- Depth of invasion into the bladder wall.

- Pathological grade of the tumor.

- Presence versus absence of carcinoma in situ.

Among nonmuscle-invasive cancers, the following factors are also prognostic:[21]

- Number of tumors.

- Tumor size (e.g., >3 cm or <3 cm).

- Invasion of the lamina propria (Ta vs. T1).

- Whether the tumor is the primary tumor or a recurrence.

Most superficial tumors are well differentiated. Patients in whom superficial tumors are less differentiated, large, multiple, or associated with carcinoma in situ (Tis) in other areas of the bladder mucosa are at greatest risk of recurrence and the development of invasive cancer. These patients may be considered to have the entire urothelial surface at risk of cancer development.

Survival

Patients who die of bladder cancer almost always have disease that has metastasized from the bladder to other organs. Low-grade bladder cancers rarely grow into the muscular wall of the bladder and rarely metastasize, so patients with low-grade (grade I) bladder cancers very rarely die of their cancer. Nonetheless, they may experience multiple relapses that need to be resected.

Almost all deaths from bladder cancer are among patients with high-grade disease, which has a much greater potential to invade deeply into the bladder's muscular wall and spread to other organs.

Approximately 70% to 80% of patients with newly diagnosed bladder cancer will present with superficial bladder tumors (i.e., stage Ta, Tis, or T1). The prognosis of these patients depends largely on the grade of the tumor. Patients with high-grade tumors have a significant risk of dying of their cancer even if it is not muscle-invasive.[22] Among patients with high-grade tumors, those who present with superficial, nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer can usually be cured, and those with muscle-invasive disease can sometimes be cured.[23,24,25] Studies have demonstrated that some patients with distant metastases have achieved long-term complete response after being treated with combination chemotherapy regimens, although most such patients have metastases limited to their lymph nodes and have a near-normal performance status.[26,27]

There are clinical trials suitable for patients with all stages of bladder cancer. Whenever possible, patients should consider clinical trials designed to improve upon standard therapy.

General information about clinical trials is also available from the NCI website.

Follow-Up

Bladder cancer tends to recur, even when it is noninvasive at the time of diagnosis; therefore, standard practice is to perform surveillance of the urinary tract after a diagnosis of bladder cancer. However, no trials have been conducted to assess whether surveillance affects rates of progression, survival, or quality of life; nor have clinical trials defined an optimal surveillance schedule. Urothelial carcinomas are thought to reflect a so-called field defect whereby the cancer emerges because of genetic mutations that are widely present in the patient's bladder or entire urothelium. Thus, people who have had a bladder tumor resected often subsequently have recurrent tumors in the bladder, often in different locations from the site of the initial tumor. Similarly, but less commonly, they may have tumors appear in the upper urinary tract (i.e., in the renal pelvises or ureters).

An alternative explanation for these patterns of recurrence is that cancer cells that are disrupted when a tumor is resected may reimplant elsewhere in the urothelium. Support for this second theory is that tumors are more likely to recur downstream than upstream from the initial cancer. Upper urinary tract cancers are more likely to recur in the bladder than bladder cancers are to recur in the upper urinary tract.[28,29,30,31]

References:

-

National Cancer Institute: SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Bladder Cancer. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute. Available online. Last accessed May 17, 2024.

-

American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2024. American Cancer Society, 2024. Available online. Last accessed June 21, 2024.

-

Burger M, Catto JW, Dalbagni G, et al.: Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. Eur Urol 63 (2): 234-41, 2013.

-

Fraumeni JF Jr, Thomas LB: Malignant bladder tumors in a man and his three sons. JAMA 201 (7): 97-9, 1967.

-

Marees T, Moll AC, Imhof SM, et al.: Risk of second malignancies in survivors of retinoblastoma: more than 40 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst 100 (24): 1771-9, 2008.

-

Gallagher DJ, Feifer A, Coleman JA: Genitourinary cancer predisposition syndromes. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 24 (5): 861-83, 2010.

-

Lindor NM, McMaster ML, Lindor CJ, et al.: Concise handbook of familial cancer susceptibility syndromes - second edition. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr (38): 1-93, 2008.

-

Stadler WM: Molecular events in the initiation and progression of bladder cancer (review). Int J Oncol 3: 549-557, 1993.

-

Brown T, Slack R, Rushton L, et al.: Occupational cancer in Britain. Urinary tract cancers: bladder and kidney. Br J Cancer 107 (Suppl 1): S76-84, 2012.

-

Nieder AM, Porter MP, Soloway MS: Radiation therapy for prostate cancer increases subsequent risk of bladder and rectal cancer: a population based cohort study. J Urol 180 (5): 2005-9; discussion 2009-10, 2008.

-

Abern MR, Dude AM, Tsivian M, et al.: The characteristics of bladder cancer after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Urol Oncol 31 (8): 1628-34, 2013.

-

Monach PA, Arnold LM, Merkel PA: Incidence and prevention of bladder toxicity from cyclophosphamide in the treatment of rheumatic diseases: a data-driven review. Arthritis Rheum 62 (1): 9-21, 2010.

-

Cosyns JP: Aristolochic acid and 'Chinese herbs nephropathy': a review of the evidence to date. Drug Saf 26 (1): 33-48, 2003.

-

Letašiová S, Medve'ová A, Šovčíková A, et al.: Bladder cancer, a review of the environmental risk factors. Environ Health 11 (Suppl 1): S11, 2012.

-

Fernández MI, López JF, Vivaldi B, et al.: Long-term impact of arsenic in drinking water on bladder cancer health care and mortality rates 20 years after end of exposure. J Urol 187 (3): 856-61, 2012.

-

Villanueva CM, Cantor KP, Grimalt JO, et al.: Bladder cancer and exposure to water disinfection by-products through ingestion, bathing, showering, and swimming in pools. Am J Epidemiol 165 (2): 148-56, 2007.

-

Kantor AF, Hartge P, Hoover RN, et al.: Urinary tract infection and risk of bladder cancer. Am J Epidemiol 119 (4): 510-5, 1984.

-

Locke JR, Hill DE, Walzer Y: Incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in patients with long-term catheter drainage. J Urol 133 (6): 1034-5, 1985.

-

Brennan P, Bogillot O, Greiser E, et al.: The contribution of cigarette smoking to bladder cancer in women (pooled European data). Cancer Causes Control 12 (5): 411-7, 2001.

-

Kirkali Z, Chan T, Manoharan M, et al.: Bladder cancer: epidemiology, staging and grading, and diagnosis. Urology 66 (6 Suppl 1): 4-34, 2005.

-

Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, et al.: Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol 49 (3): 466-5; discussion 475-7, 2006.

-

Herr HW: Tumor progression and survival of patients with high grade, noninvasive papillary (TaG3) bladder tumors: 15-year outcome. J Urol 163 (1): 60-1; discussion 61-2, 2000.

-

Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, et al.: Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol 19 (3): 666-75, 2001.

-

Madersbacher S, Hochreiter W, Burkhard F, et al.: Radical cystectomy for bladder cancer today--a homogeneous series without neoadjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol 21 (4): 690-6, 2003.

-

Manoharan M, Ayyathurai R, Soloway MS: Radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: an analysis of perioperative and survival outcome. BJU Int 104 (9): 1227-32, 2009.

-

Loehrer PJ, Einhorn LH, Elson PJ, et al.: A randomized comparison of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol 10 (7): 1066-73, 1992.

-

von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al.: Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 23 (21): 4602-8, 2005.

-

Millán-Rodríguez F, Chéchile-Toniolo G, Salvador-Bayarri J, et al.: Primary superficial bladder cancer risk groups according to progression, mortality and recurrence. J Urol 164 (3 Pt 1): 680-4, 2000.

-

Nieder AM, Brausi M, Lamm D, et al.: Management of stage T1 tumors of the bladder: International Consensus Panel. Urology 66 (6 Suppl 1): 108-25, 2005.

-

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al.: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol 54 (2): 303-14, 2008.

-

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al.: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the 2011 update. Eur Urol 59 (6): 997-1008, 2011.

Cellular Classification of Bladder Cancer

More than 90% of bladder cancers are transitional cell carcinomas derived from the uroepithelium. About 2% to 7% are squamous cell carcinomas, and 2% are adenocarcinomas.[1] Adenocarcinomas may be of urachal origin or nonurachal origin; the latter type is generally thought to arise from metaplasia of chronically irritated transitional epithelium. Small cell carcinomas also may develop in the bladder.[2,3] Sarcomas of the bladder are very rare.

Pathological grade of transitional cell carcinomas, which is based on cellular atypia, nuclear abnormalities, and the number of mitotic figures, is of great prognostic importance.

References:

-

Al-Ahmadie H, Lin O, Reuter VE: Pathology and cytology of tumors of the urinary tract. In: Scardino PT, Linehan WM, Zelefsky MJ, et al., eds.: Comprehensive Textbook of Genitourinary Oncology. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 295-316.

-

Koay EJ, Teh BS, Paulino AC, et al.: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis of small cell carcinoma of the bladder: epidemiology, prognostic variables, and treatment trends. Cancer 117 (23): 5325-33, 2011.

-

Fahed E, Hansel DE, Raghavan D, et al.: Small cell bladder cancer: biology and management. Semin Oncol 39 (5): 615-8, 2012.

Stage Information for Bladder Cancer

The clinical staging of carcinoma of the bladder is determined by the depth of invasion of the bladder wall by the tumor. This determination requires a cystoscopic examination that includes a biopsy and examination under anesthesia to assess the following:

- Size and mobility of palpable masses.

- Degree of induration of the bladder wall.

- Presence of extravesical extension or invasion of adjacent organs.

Clinical staging, even when computed tomographic (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and other imaging modalities are used, often underestimates the extent of tumor, particularly in cancers that are less differentiated and more deeply invasive. CT imaging is the standard staging modality. A clinical benefit from obtaining MRI or positron emission tomography scans instead of CT imaging has not been demonstrated.[1,2]

AJCC Stage Groupings and TNM Definitions

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has designated staging by TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification to define bladder cancer.[3]

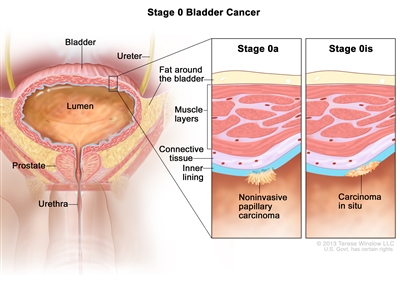

Table 1. Definitions of TNM Stages 0 and 0isa

| Stage |

TNM |

Description |

Illustration |

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. |

|

a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urinary bladder. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 757–65. |

| 0a |

Ta, N0, M0 |

Ta = Noninvasive papillary carcinoma. |

|

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis. |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

| 0is |

Tis, N0, M0 |

Tis = Urothelial carcinomain situ:flat tumor. |

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis. |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

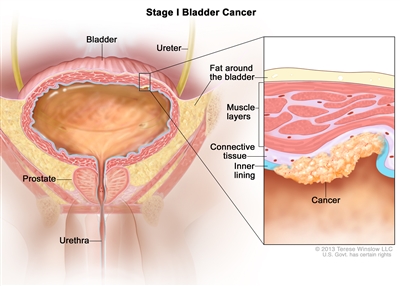

Table 2. Definition of TNM Stage Ia

| Stage |

TNM |

Description |

Illustration |

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. |

|

a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urinary bladder. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 757–65. |

| I |

T1, N0, M0 |

T1 = Tumor invades lamina propria (subepithelial connective tissue). |

|

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

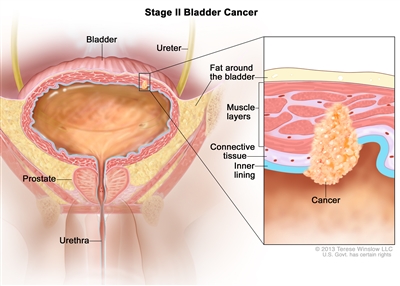

Table 3. Definition of TNM Stage IIa

| Stage |

TNM |

Description |

Illustration |

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological. |

|

a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urinary bladder. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 757–65. |

| II |

T2a, N0, M0 |

pT2a = Tumor invades superficial muscularis propria (inner half). |

|

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis. |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

| T2b, N0, M0 |

pT2b = Tumor invades deep muscularis propria (outer half). |

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis. |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

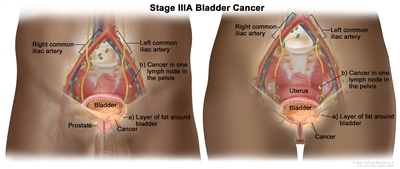

Table 4. Definition of TNM Stage IIIa

| Stage |

TNM |

Description |

Illustration |

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological. |

|

a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urinary bladder. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 757–65. |

| IIIA |

T3a, T3b, T4a, N0, M0 |

–pT3a = Microscopically. |

|

| –pT3b = Macroscopically (extravesical mass). |

| –T4a = Extravesical tumor invades directly into prostatic stroma, uterus, vagina. |

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis. |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

| T1–T4a, N1, M0 |

T1 = Tumor invades lamina propria (subepithelial connective tissue). |

| T2 = Tumor invades muscularis propria. |

| –pT2a = Tumor invades superficial muscularis propria (inner half). |

| –pT2b = Tumor invades deep muscularis propria (outer half). |

| T3 = Tumor invades perivesical soft tissue. |

| –pT3a = Microscopically. |

| –pT3b = Macroscopically (extravesical mass). |

| T4 = Extravesical tumor directly invades any of the following: prostatic stroma, seminal vesicles, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall, abdominal wall. |

| –T4a = Extravesical tumor invades directly into prostatic stroma, uterus, vagina. |

| N1 = Single regional lymph node metastasis in the true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal and external iliac, or sacral lymph node). |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

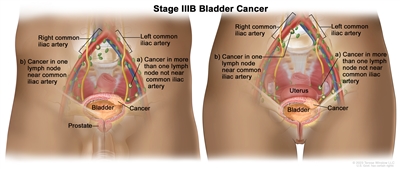

| IIIB |

T1–4a, N2, N3, M0 |

T1 = Tumor invades lamina propria (subepithelial connective tissue). |

|

| T2 = Tumor invades muscularis propria. |

| –pT2a = Tumor invades superficial muscularis propria (inner half). |

| –pT2b = Tumor invades deep muscularis propria (outer half). |

| T3 = Tumor invades perivesical soft tissue. |

| –pT3a = Microscopically. |

| pT3b = Macroscopically (extravesical mass). |

| T4 = Extravesical tumor directly invades any of the following: prostatic stroma, seminal vesicles, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall, abdominal wall. |

| –T4a = Extravesical tumor invades directly into prostatic stroma, uterus, vagina. |

| N2 = Multiple regional lymph node metastasis in the true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal and external iliac, or sacral lymph node metastasis). |

| N3 = Lymph node metastasis to the common iliac lymph nodes. |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

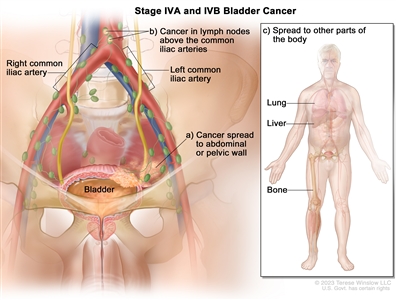

Table 5. Definition of TNM Stage IVa

| Stage |

TNM |

Description |

Illustration |

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological. |

|

a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urinary bladder. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 757–65. |

| IVA |

T4b, N0, M0 |

–T4b = Extravesical tumor invades pelvic wall, abdominal wall. |

|

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis. |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

| Any T, Any N, M1a |

TX = Primary tumor cannot be assessed. |

| T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. |

| –Ta = Noninvasive papillary carcinoma. |

| Tis = Urothelial carcinomain situ:flat tumor. |

| T1 = Tumor invades lamina propria (subepithelial connective tissue). |

| T2 = Tumor invades muscularis propria. |

| –pT2a = Tumor invades superficial muscularis propria (inner half). |

| –pT2b = Tumor invades deep muscularis propria (outer half). |

| T3 = Tumor invades perivesical soft tissue. |

| –pT3a = Microscopically. |

| –pT3b = Macroscopically (extravesical mass). |

| T4 = Extravesical tumor directly invades any of the following: prostatic stroma, seminal vesicles, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall, abdominal wall. |

| –T4a = Extravesical tumor invades directly into prostatic stroma, uterus, vagina. |

| –T4b = Extravesical tumor invades pelvic wall, abdominal wall. |

| NX = Lymph nodes cannot be assessed. |

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis. |

| N1 = Single regional lymph node metastasis in the true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal and external iliac, or sacral lymph node). |

| N2 = Multiple regional lymph node metastasis in the true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal and external iliac, or sacral lymph node metastasis). |

| N3 = Lymph node metastasis to the common iliac lymph nodes. |

| M0 = No distant metastasis. |

| –M1a = Distant metastasis limited to lymph nodes beyond the common iliacs. |

| IVB |

Any T, Any N, M1b |

TX = Primary tumor cannot be assessed. |

| T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. |

| –Ta = Noninvasive papillary carcinoma. |

| Tis = Urothelial carcinomain situ:flat tumor. |

| T1 = Tumor invades lamina propria (subepithelial connective tissue). |

| T2 = Tumor invades muscularis propria. |

| –pT2a = Tumor invades superficial muscularis propria (inner half). |

| –pT2b = Tumor invades deep muscularis propria (outer half). |

| T3 = Tumor invades perivesical soft tissue. |

| –pT3a = Microscopically. |

| –pT3b = Macroscopically (extravesical mass). |

| T4 = Extravesical tumor directly invades any of the following: prostatic stroma, seminal vesicles, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall, abdominal wall. |

| –T4a = Extravesical tumor invades directly into prostatic stroma, uterus, vagina. |

| –T4b = Extravesical tumor invades pelvic wall, abdominal wall. |

| NX = Lymph nodes cannot be assessed. |

| N0 = No lymph node metastasis. |

| N1 = Single regional lymph node metastasis in the true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal and external iliac, or sacral lymph node). |

| N2 = Multiple regional lymph node metastasis in the true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal and external iliac, or sacral lymph node metastasis). |

| N3 = Lymph node metastasis to the common iliac lymph nodes. |

| M1b = Non-lymph node distant metastases. |

For urothelial histologies, a low- and high-grade designation is used to match the current World Health Organization/International Society of Urologic Pathology recommended grading system.[3]

For squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, the grading schema in Table is recommended.[3]

Table 6. Histological Grade (G)a

| G |

G Definition |

|

a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urinary bladder. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 757–65. |

| GX |

Grade cannot be assessed. |

| G1 |

Well differentiated. |

| G2 |

Moderately differentiated. |

| G3 |

Poorly differentiated. |

References:

-

Cowan NC, Crew JP: Imaging bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol 20 (5): 409-13, 2010.

-

Green DA, Durand M, Gumpeni N, et al.: Role of magnetic resonance imaging in bladder cancer: current status and emerging techniques. BJU Int 110 (10): 1463-70, 2012.

-

Bochner BH, Hansel DE, Efstathiou JA, et al.: Urinary Bladder. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 757-65.

Treatment Option Overview for Bladder Cancer

Nonmuscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

Treatment of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancers (Ta, Tis, T1) is based on risk stratification. Essentially all patients are initially treated with transurethral resection (TUR) of the bladder tumor followed by a single immediate instillation of intravesical chemotherapy (mitomycin is typically used in the United States).[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

Subsequent therapy is based on risk and typically consists of one of the following:[6,7,8,9]

- Surveillance for relapse or recurrence (typically used for tumors with low risk of recurrence or progression).

- A minimum of 1 year of intravesical treatments with bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) plus surveillance for relapse (typically used for tumors at intermediate or high risk of progression to muscle-invasive disease).

- Additional intravesical chemotherapy (typically used for tumors with a high risk of recurrence but low risk of progression to muscle-invasive disease).

Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

Standard treatment for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancers whose goal is cure is either neoadjuvant multiagent cisplatin–based chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy and urinary diversion or radiation therapy with concomitant chemotherapy.[10,11,12,13] Other treatment approaches include the following:

- Radical cystectomy followed by multiagent cisplatin–based chemotherapy.

- Radical cystectomy without perioperative chemotherapy.[14,15,16]

- Radiation therapy without concomitant chemotherapy.[17]

- Partial cystectomy with or without perioperative chemotherapy.[18]

Many patients newly diagnosed with bladder cancer are candidates for participation in clinical trials.

Reconstructive techniques that fashion low-pressure storage reservoirs from the reconfigured small and large bowel eliminate the need for external drainage devices and, in many patients, allow voiding per urethra. These techniques are designed to improve the quality of life for patients who require cystectomy.[19]

Table 7. Treatment Options for Bladder Cancer

| Stage ( TNM Staging Criteria) |

Treatment Options |

| BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; EBRT = external-beam radiation therapy; TNM = T, size of tumor and any spread of cancer into nearby tissue; N, spread of cancer to nearby lymph nodes; M, metastasis or spread of cancer to other parts of body; TUR = transurethral resection. |

| Stage 0 Bladder Cancer |

TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy |

| TUR with fulguration |

| TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by periodic intravesical instillations of BCG |

| TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by intravesical chemotherapy |

| Segmental cystectomy(rarely indicated) |

| Radical cystectomy(in rare, highly selected patients with extensive or refractory superficial high-grade tumors) |

| Stage I Bladder Cancer |

TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy |

| TUR with fulguration |

| TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by periodic intravesical instillations of BCG |

| TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by intravesical chemotherapy |

| Segmental cystectomy(rarely indicated) |

| Radical cystectomyin selected patients with extensive or refractory superficial tumors |

| Stages II and III Bladder Cancer |

Radical cystectomy |

| Neoadjuvant combination chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy |

| Radical cystectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or immunotherapy |

| EBRT with or without concomitant chemotherapy |

| Segmental cystectomy(in selected patients) |

| TUR with fulguration(in selected patients) |

| Stage IV Bladder Cancer |

T4b, N0, M0 |

Enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab |

| Chemotherapy plus immunotherapy |

| Chemotherapy alone |

| Systemic therapy followed by radical cystectomy |

| EBRT with or without concomitant chemotherapy |

| Urinary diversion or cystectomyfor palliation |

| Any T, any N, M1 |

Enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab |

| Chemotherapy plus immunotherapy |

| Chemotherapy alone or as an adjunct to local treatment |

| Immunotherapy |

| EBRTfor palliation |

| Urinary diversion or cystectomyfor palliation |

| Other chemotherapy agents with activity in metastatic bladder cancer, such as paclitaxel, docetaxel, ifosfamide, gallium nitrate, and pemetrexed (under clinical evaluation) |

| Clinical trials |

| Recurrent Bladder Cancer |

Combination chemotherapy |

| Immunotherapy |

| Targeted therapy |

| Surgeryfor new superficial or localized tumors |

| Palliative therapy |

| Clinical trials |

Fluorouracil Dosing

The DPYD gene encodes an enzyme that catabolizes pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines, like capecitabine and fluorouracil. An estimated 1% to 2% of the population has germline pathogenic variants in DPYD, which lead to reduced DPD protein function and an accumulation of pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines in the body.[20,21] Patients with the DPYD*2A variant who receive fluoropyrimidines may experience severe, life-threatening toxicities that are sometimes fatal. Many other DPYD variants have been identified, with a range of clinical effects.[20,21,22] Fluoropyrimidine avoidance or a dose reduction of 50% may be recommended based on the patient's DPYD genotype and number of functioning DPYD alleles.[23,24,25]DPYD genetic testing costs less than $200, but insurance coverage varies due to a lack of national guidelines.[26] In addition, testing may delay therapy by 2 weeks, which would not be advisable in urgent situations. This controversial issue requires further evaluation.[27]

References:

-

Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, van der Meijden AP: A single immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol 171 (6 Pt 1): 2186-90, quiz 2435, 2004.

-

Mariappan P, Smith G: A surveillance schedule for G1Ta bladder cancer allowing efficient use of check cystoscopy and safe discharge at 5 years based on a 25-year prospective database. J Urol 173 (4): 1108-11, 2005.

-

Nieder AM, Brausi M, Lamm D, et al.: Management of stage T1 tumors of the bladder: International Consensus Panel. Urology 66 (6 Suppl 1): 108-25, 2005.

-

Oosterlinck W, Solsona E, Akaza H, et al.: Low-grade Ta (noninvasive) urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Urology 66 (6 Suppl 1): 75-89, 2005.

-

Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden A, Witjes JA, et al.: High-grade Ta urothelial carcinoma and carcinoma in situ of the bladder. Urology 66 (6 Suppl 1): 90-107, 2005.

-

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al.: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol 54 (2): 303-14, 2008.

-

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al.: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the 2011 update. Eur Urol 59 (6): 997-1008, 2011.

-

Millán-Rodríguez F, Chéchile-Toniolo G, Salvador-Bayarri J, et al.: Upper urinary tract tumors after primary superficial bladder tumors: prognostic factors and risk groups. J Urol 164 (4): 1183-7, 2000.

-

Millán-Rodríguez F, Chéchile-Toniolo G, Salvador-Bayarri J, et al.: Multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors of primary superficial bladder cancer. J Urol 163 (1): 73-8, 2000.

-

Sauer R, Birkenhake S, Kühn R, et al.: Efficacy of radiochemotherapy with platin derivatives compared to radiotherapy alone in organ-sparing treatment of bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 40 (1): 121-7, 1998.

-

Advanced Bladder Cancer Meta-analysis Collaboration: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 361 (9373): 1927-34, 2003.

-

Winquist E, Kirchner TS, Segal R, et al.: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol 171 (2 Pt 1): 561-9, 2004.

-

James ND, Hussain SA, Hall E, et al.: Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 366 (16): 1477-88, 2012.

-

Madersbacher S, Hochreiter W, Burkhard F, et al.: Radical cystectomy for bladder cancer today--a homogeneous series without neoadjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol 21 (4): 690-6, 2003.

-

Stein JP, Dunn MD, Quek ML, et al.: The orthotopic T pouch ileal neobladder: experience with 209 patients. J Urol 172 (2): 584-7, 2004.

-

Manoharan M, Ayyathurai R, Soloway MS: Radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: an analysis of perioperative and survival outcome. BJU Int 104 (9): 1227-32, 2009.

-

Widmark A, Flodgren P, Damber JE, et al.: A systematic overview of radiation therapy effects in urinary bladder cancer. Acta Oncol 42 (5-6): 567-81, 2003.

-

Holzbeierlein JM, Lopez-Corona E, Bochner BH, et al.: Partial cystectomy: a contemporary review of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience and recommendations for patient selection. J Urol 172 (3): 878-81, 2004.

-

Hautmann RE, Miller K, Steiner U, et al.: The ileal neobladder: 6 years of experience with more than 200 patients. J Urol 150 (1): 40-5, 1993.

-

Sharma BB, Rai K, Blunt H, et al.: Pathogenic DPYD Variants and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients Receiving Fluoropyrimidine Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 26 (12): 1008-1016, 2021.

-

Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E: The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 50: 9-22, 2016.

-

Shakeel F, Fang F, Kwon JW, et al.: Patients carrying DPYD variant alleles have increased risk of severe toxicity and related treatment modifications during fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 22 (3): 145-155, 2021.

-

Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al.: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103 (2): 210-216, 2018.

-

Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al.: DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1459-1467, 2018.

-

Lau-Min KS, Varughese LA, Nelson MN, et al.: Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing to guide chemotherapy dosing in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: a qualitative study of barriers to implementation. BMC Cancer 22 (1): 47, 2022.

-

Brooks GA, Tapp S, Daly AT, et al.: Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 21 (3): e189-e195, 2022.

-

Baker SD, Bates SE, Brooks GA, et al.: DPYD Testing: Time to Put Patient Safety First. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2701-2705, 2023.

Treatment of Stage 0 Bladder Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage 0 Bladder Cancer

Patients with stage 0 bladder tumors can be cured by a variety of treatments, even though the tendency for new tumor formation is high. In a series of patients with Ta or T1 tumors who were followed for a minimum of 20 years or until death, the risk of bladder cancer recurrence after initial resection was 80%.[1] Of greater concern than recurrence is the risk of progression to muscle-invasive, locally-advanced, or metastatic bladder cancer. While progression is rare for patients with low-grade tumors, it is common among patients with high-grade cancers.

One series of 125 patients with TaG3 cancers followed for 15 to 20 years reported that 39% progressed to more advanced-stage disease while 26% died of urothelial cancer. In comparison, among 23 patients with TaG1 tumors, none died and 5% progressed.[2] Risk factors for recurrence and progression are the following:[2,3,4,5,6]

- High-grade disease.

- Presence of carcinoma in situ.

- Tumor larger than 3 cm.

- Multiple tumors.

- History of prior bladder cancer.

Treatment options for stage 0 bladder cancer include the following:

- Transurethral resection (TUR) with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy.

- TUR with fulguration.

- TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by periodic intravesical instillations of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG).

- TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by intravesical chemotherapy.

- Segmental cystectomy (rarely indicated).

- Radical cystectomy (in rare, highly selected patients with extensive or refractory superficial high-grade tumors).

Transurethral resection (TUR) with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy

TUR and fulguration are the most common and conservative forms of management. Careful surveillance of subsequent bladder tumor progression is important. Because most bladder cancers recur after TUR, one immediate intravesical instillation of chemotherapy is often given after TUR. Numerous randomized controlled trials have evaluated this practice, and a meta-analysis of seven trials reported that a single intravesical treatment with chemotherapy reduced the odds of recurrence by 39% (odds ratio [OR], 0.61; P < .0001).[7,8] However, although a single instillation of chemotherapy lowers the relapse rate in patients with multiple tumors, most still relapse. Such treatment is insufficient by itself for these patients.

One retrospective series addressed the value of performing a second TUR within 2 to 6 weeks of the first TUR.[9][Level of evidence C3] A second TUR performed on 38 patients with Tis or Ta disease revealed that nine patients (24%) had lamina propria invasion (T1) and three patients (8%) had muscle invasion (T2).[9]

Such information may change the definitive management options in these individuals. Patients with extensive multifocal recurrent disease and/or other unfavorable prognostic features require more aggressive forms of treatment.

Evidence (TUR with fulguration followed by immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy):

- A 2004 meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials (1,476 patients with stage Ta or stage T1 bladder cancer) compared TUR alone with TUR followed by a single immediate intravesical instillation of chemotherapy.[7]

- The relapse rate was 48% for patients who received TUR alone and 37% for patients who received TUR plus intravesical chemotherapy (OR, 0.61; P < .0001). The risk of recurrence declined for patients with single (OR, 0.61) or multiple (OR, 0.44) tumors, but 65% of those with multiple tumors relapsed despite intravesical chemotherapy.

- Agents studied included epirubicin, mitomycin (MMC), thiotepa, and pirarubicin.

- A subsequent multicenter randomized controlled trial confirmed the reduction in risk of recurrence. A study that included 404 patients reported a relapse rate of 51% for patients who received epirubicin immediately after TUR and 63% for patients who received placebo immediately after TUR (P = .04). However, only small recurrences were prevented in this study, drawing into question the magnitude of benefit.[10]

- Similarly, another multicenter randomized controlled trial confirmed the reduction in risk of recurrence. One study randomly assigned patients (N = 305) to receive either an instillation of epirubicin or no further treatment after TUR.[8]

- The relapse rates were 62% for patients who received epirubicin and 77% for patients in the control arm (P = .016).

- The hazard ratio for recurrence was 0.56 (P = .002) with epirubicin. However, the main benefit was seen in patients at lower risk of relapse. Among patients at intermediate or high risk of relapse, the relapse rates were 81% with epirubicin versus 85% with no further treatment (P = .35).

TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by periodic intravesical instillations of BCG

Intravesical BCG is the treatment of choice for reducing the risk of cancer progression and is mainly used for cancers with an intermediate or high risk of progressing.[6,11,12,13] An individual patient meta-analysis of randomized trials compared intravesical BCG with intravesical MMC. The meta-analysis reported that there was a 32% reduction in risk of recurrence with BCG but only when the BCG treatment included a maintenance phase whereby BCG was given periodically for at least 1 year (typically an induction phase of six weekly treatments followed by three weekly treatments every 3 months).[12] Intravesical chemotherapy is tolerated better than intravesical BCG.[14,15,16,17,18] Although BCG may not prolong overall survival for Tis disease, it appears to afford complete response rates of about 70%, thereby decreasing the need for salvage cystectomy.[17] Studies show that intravesical BCG delays tumor recurrence and tumor progression.[18,19]

Intravesical therapy with thiotepa, MMC, doxorubicin, or BCG is most often used in patients with multiple tumors or recurrent tumors or as a prophylactic measure in high-risk patients after TUR.[20,21,22]

Evidence (TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by periodic intravesical instillations of BCG):

Intravesical chemotherapy

- Three meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials that compared TUR alone with TUR followed by intravesical chemotherapy reported that adjuvant therapy was associated with a statistically significant increase in time to recurrence.[23,24,25] No advantage has been shown with respect to survival or prevention of progression to invasive disease or metastases.

Intravesical BCG with maintenance BCG treatments

- An individual patient meta-analysis of nine randomized trials (2,820 patients with Ta or T1 bladder cancer) that compared intravesical BCG with intravesical MMC was published.[12]

- Among trials in which the BCG treatment included a maintenance component, there was a 32% reduction in risk of recurrence (P < .0001) compared with MMC. BCG was associated with a 28% increase in the risk of recurrence when there was no maintenance BCG administered compared with MMC.

- There were no differences in progression or death.[12]

- A meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials (2,410 patients) that compared intravesical BCG with MMC was published.[26]

- Progression was observed in 7.67% of the patients who received BCG and 9.44% of patients who received MMC at a median follow-up of 26 months (P = .08).

- When the analysis was limited to trials in which the BCG arm included a maintenance component, the progression rate was significantly lower in the patients who received BCG (OR, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.47–0.94; P = .02).

- A meta-analysis of the published results of nine randomized controlled trials that compared intravesical BCG with intravesical chemotherapy in 700 patients with carcinoma in situ of the bladder was published.[11]

- With a median follow-up of 3.6 years, 47% of the BCG group had no evidence of disease and 26% of the chemotherapy group had no evidence of disease.

- BCG was superior to MMC at preventing recurrence only when maintenance BCG was part of the treatment.

- A controlled trial evaluated 384 patients randomly assigned to induction intravesical BCG or induction intravesical BCG followed by maintenance intravesical BCG.[27]

- The median recurrence-free survival was 36 months without maintenance BCG and 77 months in the maintenance arm (P < .0001). The risk of disease worsening (progression to T2 or greater disease, use of cystectomy, systemic chemotherapy, or radiation therapy) was greater in the induction arm than in the maintenance arm (P = .04).

- The 5-year overall survival rate was 78% in the induction arm versus 83% in the maintenance arm, but this difference was not statistically significant.

BCG is associated with a risk of significant toxicity, including rare deaths from BCG sepsis. Compared with MMC, BCG produces more local toxicity (44% with BCG vs. 30% with MMC) and systemic side effects (19% with BCG vs. 12% with MMC). Because of concerns about side effects and toxicity, BCG is not generally used for patients with a low risk of progression to advanced-stage disease.[6,26]

Segmental cystectomy (rarely indicated)

Segmental cystectomy is rarely indicated.[22] It is indicated for relatively few patients because of the tendency of bladder cancer to involve multiple regions of the bladder mucosa and to occur in areas that cannot be segmentally resected. Moreover, cystectomy (whether segmental or radical) is generally not indicated for T0 bladder cancer (see radical cystectomy below).[28,29]

Radical cystectomy (in rare, highly selected patients with extensive or refractory superficial high-grade tumors)

Radical cystectomy is used in selected patients with extensive or refractory superficial tumors,[2,30,31] based on reports that up to 20% of patients with Tis will die of bladder cancer. However, cystectomy (whether segmental or radical) is generally not indicated for patients with Ta or Tis bladder cancer. Patients at high risk of progression, typically those with recurrent high-grade tumors with carcinoma in situ after intravesical therapy with BCG, should consider radical cystectomy.[32,33,34,35]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

-

Holmäng S, Hedelin H, Anderström C, et al.: The relationship among multiple recurrences, progression and prognosis of patients with stages Ta and T1 transitional cell cancer of the bladder followed for at least 20 years. J Urol 153 (6): 1823-6; discussion 1826-7, 1995.

-

Herr HW: Tumor progression and survival of patients with high grade, noninvasive papillary (TaG3) bladder tumors: 15-year outcome. J Urol 163 (1): 60-1; discussion 61-2, 2000.

-

Millán-Rodríguez F, Chéchile-Toniolo G, Salvador-Bayarri J, et al.: Upper urinary tract tumors after primary superficial bladder tumors: prognostic factors and risk groups. J Urol 164 (4): 1183-7, 2000.

-

Millán-Rodríguez F, Chéchile-Toniolo G, Salvador-Bayarri J, et al.: Multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors of primary superficial bladder cancer. J Urol 163 (1): 73-8, 2000.

-

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al.: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol 54 (2): 303-14, 2008.

-

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al.: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the 2011 update. Eur Urol 59 (6): 997-1008, 2011.

-

Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, van der Meijden AP: A single immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol 171 (6 Pt 1): 2186-90, quiz 2435, 2004.

-

Gudjónsson S, Adell L, Merdasa F, et al.: Should all patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer receive early intravesical chemotherapy after transurethral resection? The results of a prospective randomised multicentre study. Eur Urol 55 (4): 773-80, 2009.

-

Herr HW: The value of a second transurethral resection in evaluating patients with bladder tumors. J Urol 162 (1): 74-6, 1999.

-

Berrum-Svennung I, Granfors T, Jahnson S, et al.: A single instillation of epirubicin after transurethral resection of bladder tumors prevents only small recurrences. J Urol 179 (1): 101-5; discussion 105-6, 2008.

-

Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Witjes JA, et al.: Bacillus calmette-guerin versus chemotherapy for the intravesical treatment of patients with carcinoma in situ of the bladder: a meta-analysis of the published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol 174 (1): 86-91; discussion 91-2, 2005.

-

Malmström PU, Sylvester RJ, Crawford DE, et al.: An individual patient data meta-analysis of the long-term outcome of randomised studies comparing intravesical mitomycin C versus bacillus Calmette-Guérin for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol 56 (2): 247-56, 2009.

-

Stenzl A, Cowan NC, De Santis M, et al.: Treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: update of the EAU guidelines. Eur Urol 59 (6): 1009-18, 2011.

-

Herr HW, Schwalb DM, Zhang ZF, et al.: Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy prevents tumor progression and death from superficial bladder cancer: ten-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 13 (6): 1404-8, 1995.

-

Sarosdy MF, Lamm DL: Long-term results of intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy for superficial bladder cancer. J Urol 142 (3): 719-22, 1989.

-

Catalona WJ, Hudson MA, Gillen DP, et al.: Risks and benefits of repeated courses of intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy for superficial bladder cancer. J Urol 137 (2): 220-4, 1987.

-

De Jager R, Guinan P, Lamm D, et al.: Long-term complete remission in bladder carcinoma in situ with intravesical TICE bacillus Calmette Guerin. Overview analysis of six phase II clinical trials. Urology 38 (6): 507-13, 1991.

-

Herr HW, Wartinger DD, Fair WR, et al.: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy for superficial bladder cancer: a 10-year followup. J Urol 147 (4): 1020-3, 1992.

-

Lamm DL, Griffith JG: Intravesical therapy: does it affect the natural history of superficial bladder cancer? Semin Urol 10 (1): 39-44, 1992.

-

Igawa M, Urakami S, Shirakawa H, et al.: Intravesical instillation of epirubicin: effect on tumour recurrence in patients with dysplastic epithelium after transurethral resection of superficial bladder tumour. Br J Urol 77 (3): 358-62, 1996.

-

Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, et al.: A randomized trial of intravesical doxorubicin and immunotherapy with bacille Calmette-Guérin for transitional-cell carcinoma of the bladder. N Engl J Med 325 (17): 1205-9, 1991.

-

Soloway MS: The management of superficial bladder cancer. In: Javadpour N, ed.: Principles and Management of Urologic Cancer. 2nd ed. Williams and Wilkins, 1983, pp 446-467.

-

Pawinski A, Sylvester R, Kurth KH, et al.: A combined analysis of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, and Medical Research Council randomized clinical trials for the prophylactic treatment of stage TaT1 bladder cancer. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genitourinary Tract Cancer Cooperative Group and the Medical Research Council Working Party on Superficial Bladder Cancer. J Urol 156 (6): 1934-40, discussion 1940-1, 1996.

-

Huncharek M, Geschwind JF, Witherspoon B, et al.: Intravesical chemotherapy prophylaxis in primary superficial bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of 3703 patients from 11 randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol 53 (7): 676-80, 2000.

-

Huncharek M, McGarry R, Kupelnick B: Impact of intravesical chemotherapy on recurrence rate of recurrent superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: results of a meta-analysis. Anticancer Res 21 (1B): 765-9, 2001 Jan-Feb.

-

Böhle A, Bock PR: Intravesical bacille Calmette-Guérin versus mitomycin C in superficial bladder cancer: formal meta-analysis of comparative studies on tumor progression. Urology 63 (4): 682-6; discussion 686-7, 2004.

-

Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD, et al.: Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol 163 (4): 1124-9, 2000.

-

Holzbeierlein JM, Lopez-Corona E, Bochner BH, et al.: Partial cystectomy: a contemporary review of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience and recommendations for patient selection. J Urol 172 (3): 878-81, 2004.

-

Fahmy N, Aprikian A, Tanguay S, et al.: Practice patterns and recurrence after partial cystectomy for bladder cancer. World J Urol 28 (4): 419-23, 2010.

-

Amling CL, Thrasher JB, Frazier HA, et al.: Radical cystectomy for stages Ta, Tis and T1 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol 151 (1): 31-5; discussion 35-6, 1994.

-

Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden A, Witjes JA, et al.: High-grade Ta urothelial carcinoma and carcinoma in situ of the bladder. Urology 66 (6 Suppl 1): 90-107, 2005.

-

Madersbacher S, Hochreiter W, Burkhard F, et al.: Radical cystectomy for bladder cancer today--a homogeneous series without neoadjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol 21 (4): 690-6, 2003.

-

Stein JP, Dunn MD, Quek ML, et al.: The orthotopic T pouch ileal neobladder: experience with 209 patients. J Urol 172 (2): 584-7, 2004.

-

Lerner SP, Tangen CM, Sucharew H, et al.: Failure to achieve a complete response to induction BCG therapy is associated with increased risk of disease worsening and death in patients with high risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol 27 (2): 155-9, 2009 Mar-Apr.

-

Manoharan M, Ayyathurai R, Soloway MS: Radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: an analysis of perioperative and survival outcome. BJU Int 104 (9): 1227-32, 2009.

Treatment of Stage I Bladder Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage I Bladder Cancer

Patients with stage I bladder tumors are unlikely to die of bladder cancer, but the tendency for new tumor formation is high. In a series of patients with Ta or T1 tumors who were followed for a minimum of 20 years or until death, the risk of bladder recurrence after initial resection was 80%.[1] Of greater concern than recurrence is the risk of progression to muscle-invasive, locally-advanced, or metastatic bladder cancer. While progression is rare for low-grade tumors, it is common among high-grade cancers.

One series of 125 patients with TaG3 cancers followed for 15 to 20 years reported that 39% progressed to more advanced stage disease, while 26% died of urothelial cancer. In comparison, among 23 patients with TaG1 tumors, none died and 5% progressed.[2] Risk factors for recurrence and progression include the following:[2,3,4,5,6]

- High-grade disease.

- Presence of carcinoma in situ.

- Tumor larger than 3 cm.

- Multiple tumors.

- History of prior bladder cancer.

Treatment options for stage I bladder cancer include the following:

- Transurethral resection (TUR) with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy.

- TUR with fulguration.

- TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by periodic intravesical instillations of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG).

- TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by intravesical chemotherapy.

- Segmental cystectomy (rarely indicated).

- Radical cystectomy (in selected patients with extensive or refractory superficial tumors).

TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy

TUR and fulguration are the most common and conservative forms of management. Careful surveillance of subsequent bladder tumor progression is important. Because most bladder cancers recur after TUR, one immediate intravesical instillation of chemotherapy after TUR is widely used. Numerous randomized controlled trials have evaluated this practice, and a meta-analysis of seven trials reported that a single intravesical treatment with chemotherapy reduced the odds of recurrence by 39% (odds ratio [OR], 0.61; P < .0001).[7,8]

TUR with fulguration

Staging a bladder cancer via TUR is based on the extent of invasion. To assess whether cancer has invaded the muscle, muscularis propria must be present in the resected tissue. While a repeat TUR is generally considered mandatory for T1 and high-grade noninvasive bladder cancers if no muscularis propria is present in the resected tissue from the first TUR, many experts recommend that a second TUR be routinely performed within 2 to 6 weeks of the first TUR to confirm staging and achieve a more complete resection. The rationale for this derives from numerous findings, including the following:

- The risk of local recurrence after TUR is high.

- Residual cancer is often found when a repeat TUR is performed.

- More-advanced–stage cancer is sometimes found with repeat TUR.

- Patients undergoing radical cystectomy for nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer are often found to have T2 or greater disease when the cystectomy specimen is examined.

- A substantial number of patients with high-grade nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer subsequently die of their disease.

Evidence (routine repeat TUR):

- A review of more than 2,400 patients from over 60 different institutions reported a 3-month recurrence rate of roughly 14% to 20% after TUR, while a literature review reported that up to 10% of patients who underwent a second TUR for Ta to T1 cancer were upstaged to T2.[9] The likelihood of being upstaged to T2 is much higher when no muscularis propria is present in the initial TUR tissue.[10]

- One retrospective series of 38 patients with Tis or Ta disease who underwent a second TUR found that nine patients (24%) had lamina propria invasion (T1) and three patients (8%) had muscle invasion (T2).[11]

- A subsequent study from a different institution reported that among 214 patients with Ta to T1 cancers who underwent a second TUR, 27% of Ta and 37% of T1 patients had residual cancer detected.[12]

- A review of other published papers reported that residual tumor was present in 27% to 62% of cases, and muscle-invasive disease was discovered in 1% to 10% of case series with at least 50 patients.[10]

Repeat TUR has not been shown to reduce relapse rates or prolong survival, but there is a clear rationale for seeking accurate staging information on which to base treatment decisions. Such information may change the definitive management options for patients and identify patients who are more likely to benefit from more aggressive treatment.

TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by periodic intravesical instillations of BCG

Intravesical BCG is the treatment of choice for reducing the risk of cancer progression and is mainly used for cancers with an intermediate or high risk of progressing.[6,13,14,15] An individual patient meta-analysis of randomized trials that compared intravesical BCG with intravesical mitomycin (MMC) reported that there was a 32% reduction in risk of recurrence with BCG but only when the BCG treatment included a maintenance phase whereby BCG was given periodically for at least 1 year (typically an induction phase of six weekly treatments followed by three weekly treatments every 3 months).[14] Intravesical chemotherapy is tolerated better than intravesical BCG.[16,17,18,19,20] Although BCG may not prolong overall survival for Tis disease, it appears to afford complete response rates of about 70%, thereby decreasing the need for salvage cystectomy.[19] Studies show that intravesical BCG delays tumor recurrence and tumor progression.[20,21]

Evidence (immediate intravesical chemotherapy after transurethral resection):

- A 2004 meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials (1,476 patients with Ta or T1 bladder cancer) compared TUR alone with TUR followed by a single immediate intravesical instillation of chemotherapy. Agents studied included epirubicin, MMC, thiotepa, and pirarubicin.[7]

- The relapse rates were 48% for patients who received TUR alone and 37% for patients who received TUR plus intravesical chemotherapy (OR, 0.61; P < .0001). The risk of recurrence declined for patients with single (OR, 0.61) or multiple (OR, 0.44) tumors, but 65% of those with multiple tumors relapsed despite intravesical chemotherapy.

- A subsequent multicenter randomized controlled trial confirmed the reduction in risk of recurrence. A study that included 404 patients reported a relapse rate of 51% for patients who received epirubicin immediately after TUR and 63% for patients who received placebo immediately after TUR (P = .04). However, only small recurrences were prevented in this study, drawing into question the magnitude of benefit.[22]

- Similarly, another multicenter randomized controlled trial confirmed the reduction in risk of recurrence. One study randomly assigned patients (N = 305) to receive either an instillation of epirubicin or no further treatment after TUR.[8]

- The relapse rates were 62% for patients who received epirubicin and 77% for patients in the control arm (P = .016).

- The hazard ratio for recurrence was 0.56 (P = .002) with epirubicin. However, the main benefit was seen in patients at lower risk of relapse. Among patients at intermediate or high risk of relapse, the relapse rates were 81% with epirubicin versus 85% with no further treatment (P = .35).

Evidence (intravesical BCG with maintenance BCG treatments):

- An individual patient meta-analysis of nine randomized trials (2,820 patients with Ta or T1 bladder cancer) that compared intravesical BCG with intravesical MMC was published.[14]

- Among trials in which the BCG treatment included a maintenance component, there was a 32% reduction in risk of recurrence (P < .0001) compared with MMC. BCG was associated with a 28% increase in the risk of recurrence when no maintenance BCG was given compared with MMC.

- There were no differences in progression or death.

- A meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials (2,410 patients) that compared intravesical BCG with MMC was published.[23]

- Progression was seen in 7.67% of the patients who received BCG and 9.44% of patients who received MMC at a median follow-up of 26 months (P = .08).

- When the analysis was limited to trials in which the BCG arm included a maintenance component, the progression rate was significantly lower in the patients who received BCG (OR, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.47–0.94; P = .02).

- A meta-analysis of the published results of nine randomized controlled trials that compared intravesical BCG with intravesical chemotherapy in 700 patients with carcinoma in situ of the bladder was published.[13]

- With a median follow-up of 3.6 years, 47% of the BCG group had no evidence of disease and 26% of the chemotherapy group had no evidence of disease.

- In this meta-analysis, BCG was superior to MMC at preventing recurrence only when maintenance BCG was part of the treatment.

- A controlled trial evaluated 384 patients randomly assigned to induction intravesical BCG or induction intravesical BCG followed by maintenance intravesical BCG.[24]

- Median recurrence-free survival was 36 months without maintenance BCG and 77 months in the maintenance arm (P < .0001). The risk of disease worsening (progression to T2 or greater disease, use of cystectomy, systemic chemotherapy, or radiation therapy) was greater in the induction arm than in the maintenance arm (P = .04).

- The 5-year overall survival rate was 78% in the induction arm versus 83% in the maintenance arm, but this difference was not statistically significant.

BCG is associated with a risk of significant toxicity, including rare deaths from BCG sepsis. Compared with MMC, BCG produces more local toxicity (44% with BCG vs. 30% with MMC) and systemic side effects (19% with BCG vs. 12% with MMC). Because of concerns about side effects and toxicity, BCG is not generally used for patients with a low risk of progression to more-advanced–stage disease.[6,23]

Evidence (two treatment courses of intravesical BCG):

- Two nonconsecutive 6-week courses with BCG may be necessary to obtain optimal response.[25] Patients with a T1 tumor at the 3-month evaluation after a 6-week course of BCG and patients with Tis that persists after a second 6-week BCG course have a high likelihood of developing muscle-invasive disease and should be considered for cystectomy.[18,25,26]

TUR with fulguration followed by an immediate postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by intravesical chemotherapy

Intravesical therapy with thiotepa, MMC, doxorubicin, or BCG is most often used in patients with multiple tumors or recurrent tumors or as a prophylactic measure in high-risk patients after TUR.[27,28]

Evidence (intravesical chemotherapy):

- Three meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials that compared TUR alone with TUR followed by intravesical chemotherapy reported that adjuvant therapy was associated with a statistically significant increase in time to recurrence. No advantage has been shown with respect to survival or prevention of progression to invasive disease or metastases.[29,30,31]

- One analysis of eight studies with a combined total of 1,609 patients reported that intravesical chemotherapy reduced the risk of relapse at 1 year by 38% and by as much as 70% at 3 years, depending on which drugs were used.[30]

- Another analysis of 11 studies that enrolled a total of 3,703 patients reported a 44% reduction in 1-year recurrence rates.[30]

- An earlier study of 2,535 patients enrolled in six different randomized controlled trials reported a decreased risk of recurrence but not significant benefit with regard to risk of progression to more-advanced–stage disease or survival.[29]

Segmental cystectomy (rarely indicated)

Segmental cystectomy is rarely indicated.[32] It is indicated for relatively few patients because of the tendency of bladder carcinoma to involve multiple regions of the bladder mucosa and to occur in areas that cannot be segmentally resected. Moreover, cystectomy (whether segmental or radical) is generally not indicated for patients with T0 bladder cancer.[33,34]

Radical cystectomy in selected patients with extensive or refractory superficial tumors

Radical cystectomy is used in selected patients with extensive or refractory superficial tumors.[35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] Patients at high risk of progression, typically those with recurrent high-grade tumors with carcinoma in situ after intravesical therapy with BCG, should consider radical cystectomy. Other risk factors include multiple tumors and tumors larger than 3 cm.

Certain patients with nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer face a substantial risk of progression and death from their cancers.

Evidence (radical cystectomy):

- One analysis of 307 patients enrolled in studies of intravesical BCG in the 1980s reported that among 85 patients with T1 recurrence, 60 progressed to at least stage II disease. Five years after T1 recurrence, 71% had progressed and 48% had died of their cancer.[44]

- By comparison, in another cohort of 589 patients treated with BCG between 1992 and 2004, 65 of the 120 patients with T1 recurrence underwent immediate cystectomy. Among all patients with T1 recurrence, 28% progressed to more-advanced–stage disease and 31% died of their cancer. While these data confirm that patients with recurring cancer after intravesical BCG face a substantial risk of dying of their disease, they do not provide strong evidence that immediate cystectomy results in a lower risk of death or progression.[44]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

-

Holmäng S, Hedelin H, Anderström C, et al.: The relationship among multiple recurrences, progression and prognosis of patients with stages Ta and T1 transitional cell cancer of the bladder followed for at least 20 years. J Urol 153 (6): 1823-6; discussion 1826-7, 1995.

-

Herr HW: Tumor progression and survival of patients with high grade, noninvasive papillary (TaG3) bladder tumors: 15-year outcome. J Urol 163 (1): 60-1; discussion 61-2, 2000.

-

Millán-Rodríguez F, Chéchile-Toniolo G, Salvador-Bayarri J, et al.: Upper urinary tract tumors after primary superficial bladder tumors: prognostic factors and risk groups. J Urol 164 (4): 1183-7, 2000.

-

Millán-Rodríguez F, Chéchile-Toniolo G, Salvador-Bayarri J, et al.: Multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors of primary superficial bladder cancer. J Urol 163 (1): 73-8, 2000.

-

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al.: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol 54 (2): 303-14, 2008.

-

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al.: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the 2011 update. Eur Urol 59 (6): 997-1008, 2011.

-

Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, van der Meijden AP: A single immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol 171 (6 Pt 1): 2186-90, quiz 2435, 2004.

-

Gudjónsson S, Adell L, Merdasa F, et al.: Should all patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer receive early intravesical chemotherapy after transurethral resection? The results of a prospective randomised multicentre study. Eur Urol 55 (4): 773-80, 2009.

-

Brausi M, Collette L, Kurth K, et al.: Variability in the recurrence rate at first follow-up cystoscopy after TUR in stage Ta T1 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a combined analysis of seven EORTC studies. Eur Urol 41 (5): 523-31, 2002.

-

Jakse G, Algaba F, Malmström PU, et al.: A second-look TUR in T1 transitional cell carcinoma: why? Eur Urol 45 (5): 539-46; discussion 546, 2004.

-

Herr HW: The value of a second transurethral resection in evaluating patients with bladder tumors. J Urol 162 (1): 74-6, 1999.

-

Zurkirchen MA, Sulser T, Gaspert A, et al.: Second transurethral resection of superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a must even for experienced urologists. Urol Int 72 (2): 99-102, 2004.

-

Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Witjes JA, et al.: Bacillus calmette-guerin versus chemotherapy for the intravesical treatment of patients with carcinoma in situ of the bladder: a meta-analysis of the published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol 174 (1): 86-91; discussion 91-2, 2005.

-

Malmström PU, Sylvester RJ, Crawford DE, et al.: An individual patient data meta-analysis of the long-term outcome of randomised studies comparing intravesical mitomycin C versus bacillus Calmette-Guérin for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol 56 (2): 247-56, 2009.

-

Stenzl A, Cowan NC, De Santis M, et al.: Treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: update of the EAU guidelines. Eur Urol 59 (6): 1009-18, 2011.

-